L-99: Ninety-Nine Lisp Problems

Based on a Prolog problem list by werner.hett@hti.bfh.ch

Working with lists

- P01

(*) Find the last box of a list.

- Example:

* (my-last '(a b c d))

(D)

- P02

(*) Find the last but one box of a list.

- Example:

* (my-but-last '(a b c d))

(C D)

- P03

(*) Find the K'th element of a list.

- The first element in the list is number 1.

Example:

* (element-at '(a b c d e) 3)

C

- P04

(*) Find the number of elements of a list.

- P05

(*) Reverse a list.

- P06

(*) Find out whether a list is a palindrome.

- A palindrome can be read forward or backward; e.g. (x a m a x).

- P07

(**) Flatten a nested list structure.

- Transform a list, possibly holding lists as elements into a `flat'

list by replacing each list with its elements (recursively).

Example:

* (my-flatten '(a (b (c d) e)))

(A B C D E)

Hint: Use the predefined functions list and append.

- P08

(**) Eliminate consecutive duplicates of list elements.

- If a list contains repeated elements they should be replaced

with a single copy of the element. The order of the elements should

not be changed.

Example:

* (compress '(a a a a b c c a a d e e e e))

(A B C A D E)

- P09

(**) Pack consecutive duplicates of list elements into sublists.

- If a list contains repeated elements they should be placed

in separate sublists.

Example:

* (pack '(a a a a b c c a a d e e e e))

((A A A A) (B) (C C) (A A) (D) (E E E E))

- P10

(*) Run-length encoding of a list.

- Use the result of problem P09 to implement the so-called

run-length encoding data compression method. Consecutive duplicates

of elements are encoded as lists (N E) where N is the number

of duplicates of the element E.

Example:

* (encode '(a a a a b c c a a d e e e e))

((4 A) (1 B) (2 C) (2 A) (1 D)(4 E))

- P11

(*) Modified run-length encoding.

- Modify the result of problem P10 in such a way that if an element

has no duplicates it is simply copied into the result list. Only

elements with duplicates are transferred as (N E) lists.

Example:

* (encode-modified '(a a a a b c c a a d e e e e))

((4 A) B (2 C) (2 A) D (4 E))

- P12

(**) Decode a run-length encoded list.

- Given a run-length code list generated as specified

in problem P11. Construct its uncompressed version.

- P13

(**) Run-length encoding of a list (direct solution).

- Implement the so-called run-length encoding data compression

method directly. I.e. don't explicitly create the sublists

containing the duplicates, as in problem P09, but only count them.

As in problem P11, simplify the result list by replacing the singleton

lists (1 X) by X.

Example:

* (encode-direct '(a a a a b c c a a d e e e e))

((4 A) B (2 C) (2 A) D (4 E))

- P14

(*) Duplicate the elements of a list.

- Example:

* (dupli '(a b c c d))

(A A B B C C C C D D)

- P15

(**) Replicate the elements of a list a given number of times.

- Example:

* (repli '(a b c) 3)

(A A A B B B C C C)

- P16

(**) Drop every N'th element from a list.

- Example:

* (drop '(a b c d e f g h i k) 3)

(A B D E G H K)

- P17

(*) Split a list into two parts; the length of the first

part is given.

- Do not use any predefined functions.

Example:

* (split '(a b c d e f g h i k) 3)

( (A B C) (D E F G H I K))

- P18

(**) Extract a slice from a list.

- Given two indices, I and K, the slice is the list

containing the elements between the I'th and K'th element

of the original list (both limits included). Start counting

the elements with 1.

Example:

* (slice '(a b c d e f g h i k) 3 7)

(C D E F G)

- P19

(**) Rotate a list N places to the left.

- Examples:

* (rotate '(a b c d e f g h) 3)

(D E F G H A B C)

* (rotate '(a b c d e f g h) -2)

(G H A B C D E F)

Hint: Use the predefined functions length and append,

as well as the result of problem P17.

- P20

(*) Remove the K'th element from a list.

- Example:

* (remove-at '(a b c d) 2)

(A C D)

- P21

(*) Insert an element at a given position into a list.

- Example:

* (insert-at 'alfa '(a b c d) 2)

(A ALFA B C D)

- P22

(*) Create a list containing all integers within a given range.

- If first argument is smaller than second, produce a list in

decreasing order.

- Example:

* (range 4 9)

(4 5 6 7 8 9)

- P23

(**) Extract a given number of randomly selected elements from a

list.

- The selected items shall be returned in a list.

Example:

* (rnd-select '(a b c d e f g h) 3)

(E D A)

Hint: Use the built-in random number generator and the

result of problem P20.

- P24

(*) Lotto: Draw N different random numbers from the set 1..M.

- The selected numbers shall be returned in a list.

Example:

* (lotto-select 6 49)

(23 1 17 33 21 37)

Hint: Combine the solutions of problems P22 and P23.

- P25

(*) Generate a random permutation of the elements of a list.

- Example:

* (rnd-permu '(a b c d e f))

(B A D C E F)

Hint: Use the solution of problem P23.

- P26

(**) Generate the combinations of K distinct objects

chosen from the N elements of a list

-

In how many ways can a committee of 3 be chosen from a group of

12 people? We all know that there are C(12,3) = 220 possibilities

(C(N,K) denotes the well-known binomial coefficients). For pure

mathematicians, this result may be great. But we want to

really generate all the possibilities in a list.

Example:

* (combination 3 '(a b c d e f))

((A B C) (A B D) (A B E) ... )

- P27

(**) Group the elements of a set into disjoint subsets.

-

a) In how many ways can a group of 9 people work in 3 disjoint subgroups

of 2, 3 and 4 persons? Write a function that generates all the

possibilities and returns them in a list.

Example:

* (group3 '(aldo beat carla david evi flip gary hugo ida))

( ( (ALDO BEAT) (CARLA DAVID EVI) (FLIP GARY HUGO IDA) )

... )

b) Generalize the above function in a way that we can specify a list

of group sizes and the function will return a list of groups.

Example:

* (group '(aldo beat carla david evi flip gary hugo ida) '(2 2 5))

( ( (ALDO BEAT) (CARLA DAVID) (EVI FLIP GARY HUGO IDA) )

... )

Note that we do not want permutations of the group members; i.e.

((ALDO BEAT) ...) is the same solution as ((BEAT ALDO) ...). However,

we make a difference between ((ALDO BEAT) (CARLA DAVID) ...) and

((CARLA DAVID) (ALDO BEAT) ...).

You may find more about this combinatorial problem in a good book

on discrete mathematics under the term "multinomial coefficients".

- P28

(**) Sorting a list of lists according to length of sublists

-

a) We suppose that a list contains elements that are

lists themselves. The objective is to sort the elements of this list

according to their length. E.g. short lists first, longer lists

later, or vice versa.

Example:

* (lsort '((a b c) (d e) (f g h) (d e) (i j k l) (m n) (o)))

((O) (D E) (D E) (M N) (A B C) (F G H) (I J K L))

b) Again, we suppose that a list contains elements that are

lists themselves. But this time the objective is to sort the elements

of this list according to their length frequency; i.e.,

in the default,

where sorting is done ascendingly, lists with rare lengths are placed

first, others with a more frequent length come later.

Example:

* (lfsort '((a b c) (d e) (f g h) (d e) (i j k l) (m n) (o)))

((I J K L) (O) (A B C) (F G H) (D E) (D E) (M N))

Note that in the above example, the first two lists in the result

have length 4 and 1, both lengths appear just once. The third and

forth list have length 3 which appears twice (there are two list of this

length). And finally, the last three lists have length 2. This is

the most frequent length.

Arithmetic

- P31

(**) Determine whether a given integer number is prime.

- Example:

* (is-prime 7)

T

- P32

(**) Determine the greatest common divisor of two positive integer

numbers.

- Use Euclid's algorithm.

Example:

* (gcd 36 63)

9

- P33

(*) Determine whether two positive integer numbers are coprime.

- Two numbers are coprime if their greatest common divisor equals 1.

Example:

* (coprime 35 64)

T

- P34

(**) Calculate Euler's totient function phi(m).

- Euler's so-called totient function phi(m) is defined as the number

of positive integers r (1 <= r < m) that are coprime to m.

Example: m = 10: r = 1,3,7,9; thus phi(m) = 4.

Note the special case: phi(1) = 1.

* (totient-phi 10)

4

Find out what the value of phi(m) is if m is a prime number.

Euler's totient function plays an important role in one of the

most widely used public key cryptography methods (RSA). In this

exercise you should use the most primitive method to calculate

this function (there are smarter ways that we shall discuss later).

- P35

(**) Determine the prime factors of a given positive integer.

- Construct a flat list containing the prime factors

in ascending order.

Example:

* (prime-factors 315)

(3 3 5 7)

- P36

(**) Determine the prime factors of a given positive integer (2).

- Construct a list containing the prime factors and

their multiplicity.

Example:

* (prime-factors-mult 315)

((3 2) (5 1) (7 1))

Hint: The problem is similar to problem

P10.

- P37

(**) Calculate Euler's totient function phi(m) (improved).

- See problem P34 for the definition of Euler's totient function.

If the list of the prime factors of a number m is known in the form

of problem P36 then the function phi(m) can be efficiently

calculated as follows:

Let ((p1 m1) (p2 m2) (p3 m3) ...) be the list of prime factors (and

their multiplicities) of a given number m. Then phi(m) can be calculated

with the following formula:

phi(m) = (p1 - 1) * p1 ** (m1 - 1) * (p2 - 1) * p2 ** (m2 - 1) *

(p3 - 1) * p3 ** (m3 - 1) * ...

Note that a ** b stands for the b'th power of a.

- P38

(*) Compare the two methods of calculating Euler's totient function.

- Use the solutions of problems P34 and P37 to compare the algorithms.

Take the number of basic operations, including CARs, CDRs, CONSes, and

arithmetic operations, as a measure for efficiency.

Try to calculate phi(10090) as an example.

- P39

(*) A list of prime numbers.

- Given a range of integers by its lower and upper limit, construct

a list of all prime numbers in that range.

- P40

(**) Goldbach's conjecture.

- Goldbach's conjecture says that every positive even number

greater than 2 is the sum of two prime numbers. Example: 28 = 5 + 23.

It is one of the most famous facts in number theory that has not

been proved to be correct in the general case.

It has been numerically

confirmed up to very large numbers (much larger than we can go with our

Lisp system). Write a function to find the two prime numbers

that sum up to a given even integer.

Example:

* (goldbach 28)

(5 23)

- P41

(**) A list of Goldbach compositions.

- Given a range of integers by its lower and upper limit, print

a list of all even numbers and their Goldbach composition.

Example:

* (goldbach-list 9 20)

10 = 3 + 7

12 = 5 + 7

14 = 3 + 11

16 = 3 + 13

18 = 5 + 13

20 = 3 + 17

In most cases, if an even number is written as the sum of two

prime numbers, one of them is very small. Very rarely, the primes

are both bigger than say 50. Try to find out how many such cases

there are in the range 2..3000.

Example (for a print limit of 50):

* (goldbach-list 1 2000 50)

992 = 73 + 919

1382 = 61 + 1321

1856 = 67 + 1789

1928 = 61 + 1867

Logic and Codes

- P46

(**) Truth tables for logical expressions.

- Define functions and, or, nand, nor, xor, impl

and equ (for logical equivalence) which return the result

of the respective operation on boolean values.

A logical expression in two variables can then be written in

prefix notation, as in the following example: (and (or A B) (nand

A B)).

Write a function table which prints the truth table of a

given logical expression in two variables.

Example:

* (table 'A 'B '(and A (or A B))).

true true true

true nil true

nil true nil

nil nil nil

- P47

(*) Truth tables for logical expressions (2).

- Modify problem P46 by accepting expressions written in

infix notation, with all parenthesis present.

This allows us to write logical expression in a

more natural way, as in the example: (A and (A or (not B))).

Example:

* (table 'A 'B '(A and (A or (not B)))).

true true true

true nil true

nil true nil

nil nil nil

- P48

(**) Truth tables for logical expressions (3).

- Generalize problem P47 in such a way that the logical

expression may contain any number of logical variables.

Define table in a way that (table List Expr) prints the

truth table for the expression Expr, which contains the

logical variables enumerated in List.

Example:

* (table '(A B C) '((A and (B or C)) equ ((A and B) or (A and C)))).

true true true true

true true nil true

true nil true true

true nil nil true

nil true true true

nil true nil true

nil nil true true

nil nil nil true

- P49

(**) Gray code.

- An n-bit Gray code is a sequence of n-bit strings constructed

according to certain rules. For example,

n = 1: C(1) = ("0" "1").

n = 2: C(2) = ("00" "01" "11" "10").

n = 3: C(3) = ("000" "001" "011" "010" "110" "111" "101" "100").

Find out the construction rules and write a function with the following

specification:

(gray N) returns the N-bit Gray code

Can you apply the method of "result caching" in order to make the function

more efficient, when it is to be used repeatedly?

- P50

(***) Huffman code.

- First of all, consult a good book on discrete mathematics or

algorithms for a detailed description of Huffman codes!

We suppose a set of symbols with their frequencies, given as a list of

(S F) elements. Example:

( (a 45) (b 13) (c 12) (d 16) (e 9) (f 5) ). Our objective is to

construct a list of (S C) elements, where C is the Huffman code word for

symbol S. In our example, the result could be ( (A "0") (B "101")

(C "100") (D "111") (E "1101") (F "1100") ).

The task shall be performed by a function huffman defined as follows:

(huffman F) returns the Huffman code table for the frequency table F

Binary Trees

A binary tree is either empty or it is composed of a root

element and two successors, which are binary trees themselves.

In Lisp we represent the empty tree by 'nil' and the

non-empty tree by the list (X L R), where X denotes the information at the root

node and L and R denote the left and right subtrees, respectively.

The example tree depicted opposite is therefore represented by the

following list:

(a (b (d nil nil) (e nil nil)) (c nil (f (g nil nil) nil)))

Other examples are a binary tree that consists of a root node only:

(a nil nil) or an empty binary tree: nil.

You can check your functions using these example trees. They are

given as test cases in p54.lisp.

- P54A

(*) Check whether a given expression represents a binary tree

- Write a function istree which returns true if and only if its argument

is a list representing a binary tree.

Example:

* (istree '(a (b nil nil) nil))

T

* (istree '(a (b nil nil)))

NIL

- P55

(**) Construct completely balanced binary trees

- In a completely balanced binary tree, the following property holds for

every node: The number of nodes in its left subtree and the number of

nodes in its right subtree are almost equal, which means their

difference is not greater than one.

Write a function cbal-tree to construct completely balanced

binary trees for a given number of nodes. The function should

generate all solutions. Put the symbol 'x'

as information into all nodes of the tree.

Example:

* (cbal-tree-print 4)

(X (X NIL NIL) (X NIL (X NIL NIL)))

(X (X NIL NIL) (X (X NIL NIL) NIL))

etc......

Note: you can either print the trees or return a list

with them all.

* (cbal-tree 4)

((X (X NIL NIL) (X NIL (X NIL NIL))) (X (X NIL NIL) (X (X NIL NIL) NIL))

......)

- P56

(**) Symmetric binary trees

- Let us call a binary tree symmetric if you can draw a vertical

line through the root node and then the right subtree is the mirror

image of the left subtree.

Write a function symmetric to check whether a given binary

tree is symmetric.

We are only interested in the structure, not in the contents

of the nodes.

- P57

(**) Binary search trees (dictionaries)

- Write a function to construct a binary search tree

from a list of integer numbers.

Example:

* (construct '(3 2 5 7 1))

(3 (2 (1 nil nil) nil) (5 nil (7 nil nil)))

Then use this function to test the solution of the problem P56.

Example:

* (symmetric '(5 3 18 1 4 12 21))

T

* (symmetric '(3 2 5 7 1))

T

* (symmetric '(3 2 5 7))

NIL

- P58

(**) Generate-and-test paradigm

- Apply the generate-and-test paradigm to construct all symmetric,

completely balanced binary trees with a given number of nodes.

Example:

* (sym-cbal-trees-print 5)

(X (X NIL (X NIL NIL)) (X (X NIL NIL) NIL))

(X (X (X NIL NIL) NIL) (X NIL (X NIL NIL)))

...

How many such trees are there with 57 nodes? Investigate about

how many solutions there are for a given number of nodes. What if

the number is even? Write an appropriate function.

- P59

(**) Construct height-balanced binary trees

- In a height-balanced binary tree, the following property holds for

every node: The height of its left subtree and the height of

its right subtree are almost equal, which means their

difference is not greater than one.

Write a function hbal-tree to construct height-balanced

binary trees for a given height. The function should

generate all solutions. Put the letter 'x'

as information into all nodes of the tree.

Example:

* (hbal-tree 3)

(X (X (X NIL NIL) (X NIL NIL)) (X (X NIL NIL) (X NIL NIL)))

= (X (X (X NIL NIL) (X NIL NIL)) (X (X NIL NIL) NIL))

etc......

- P60

(**) Construct height-balanced binary trees with a given number of nodes

- Consider a height-balanced binary tree of height H. What is the

maximum number of nodes it can contain?

Clearly, MAXN = 2**H - 1.

However, what is the minimum number MINN? This question is more

difficult. Try to find a recursive statement and turn it into a

function minnodes defined as follows:

(min-nodes H) returns the minimum number of nodes in a

height-balanced binary tree of height H.

On the other hand, we might ask: what is the maximum height H a

height-balanced binary tree with N nodes can have?

(max-height N) returns the maximum height of a height-balanced

binary tree with N nodes

Now, we can attack the main problem: construct all the

height-balanced binary trees with a given number of nodes.

(hbal-tree-nodes N) returns all height-balanced binary trees with

N nodes.

Find out how many height-balanced trees exist for N = 15.

- P61

(*) Count the leaves of a binary tree

- A leaf is a node with no successors. Write a function

count-leaves to count them.

(count-leaves tree) returns the number of leaves of binary tree tree

- P61A

(*) Collect the leaves of a binary tree in a list

- A leaf is a node with no successors. Write a function

leaves to return them in a list.

(leaves tree) returns the list of all leaves of the binary tree tree

- P62

(*) Collect the internal nodes of a binary tree in a list

- An internal node of a binary tree has either one or two non-empty

successors. Write a function internals to collect

them in a list.

(internals tree) returns the list of internal nodes of

the binary tree tree.

- P62B

(*) Collect the nodes at a given level in a list

- A node of a binary tree is at level N if the path from the

root to the node has length N-1. The root node is at level 1.

Write a function atlevel to collect all nodes at a given

level in a list.

(atlevel tree L) returns the list of nodes of the binary tree

tree at level L

Using atlevel it is easy to construct a function levelorder

which creates the level-order sequence of the nodes. However,

there are more efficient ways to do that.

- P63

(**) Construct a complete binary tree

- A complete binary tree with height H is

defined as follows: The levels 1,2,3,...,H-1 contain the

maximum number of nodes (i.e 2**(i-1) at the level i, note

that we start counting the levels from 1 at the root).

In level H, which may contain less than the maximum possible number

of nodes, all the nodes are "left-adjusted". This means

that in a levelorder tree traversal all internal nodes come

first, the leaves come second, and empty successors (the nil's

which are not really nodes!) come last.

Particularly, complete binary trees are used as data structures

(or addressing schemes) for heaps.

We can assign an address number to each node in a complete

binary tree by enumerating the nodes in levelorder, starting

at the root with number 1. In doing so, we realize that for

every node X with address A the following property holds:

The address of X's left and right successors are 2*A and 2*A+1,

respectively, supposed the successors do exist. This fact can

be used to elegantly construct a complete binary tree structure.

Write a function complete-binary-tree with the following

specification:

(complete-binary-tree N) returns a complete binary tree with

N nodes

Test your function in an appropriate way.

- P64

(**) Layout a binary tree (1)

- Consider a binary tree as the usual symbolic expression (X L R) or nil.

As a preparation for drawing the tree, a layout algorithm is

required to determine the position of each node in a rectangular

grid. Several layout methods are conceivable, one of them is

shown in the illustration below.

In this layout strategy, the position of a node v

is obtained by the following two rules:

In this layout strategy, the position of a node v

is obtained by the following two rules:

- x(v) is equal to the position of the node v

in the inorder sequence

- y(v) is equal to the depth of the node v in

the tree

In order to store the position of the nodes, we extend the symbolic

expression representing a node (and its successors) as follows:

nil represents the empty tree (as usual)

(W X Y L R) represents a (non-empty) binary tree with root

W "positioned" at (X,Y), and subtrees L and R

Write a function layout-binary-tree with the following

specification:

(layout-binary-tree tree) returns the "positioned" binary

tree obtained from the binary tree tree

Test your function in an appropriate way.

- P65

(**) Layout a binary tree (2)

An alternative layout method is depicted in the illustration

opposite. Find out the rules and write the corresponding

Lisp function. Hint: On a given level, the horizontal

distance between neighboring nodes is constant.

An alternative layout method is depicted in the illustration

opposite. Find out the rules and write the corresponding

Lisp function. Hint: On a given level, the horizontal

distance between neighboring nodes is constant.

Use the same conventions as in problem P64 and test your

function in an appropriate way.

- P66

(***) Layout a binary tree (3)

Yet another layout strategy is shown in the illustration

opposite. The method yields a very compact layout while

maintaining a certain symmetry in every node. Find out

the rules and write the corresponding Lisp function.

Hint: Consider the horizontal distance between a node and its

successor nodes. How tight can you pack together two subtrees to

construct the combined binary tree?

Yet another layout strategy is shown in the illustration

opposite. The method yields a very compact layout while

maintaining a certain symmetry in every node. Find out

the rules and write the corresponding Lisp function.

Hint: Consider the horizontal distance between a node and its

successor nodes. How tight can you pack together two subtrees to

construct the combined binary tree?

Use the same conventions as in problem P64 and P65 and

test your function in an appropriate way. Note: This is

a difficult problem. Don't give up too early!

Which layout do you like most?

- P67

(**) A string representation of binary trees

Somebody represents binary trees as strings of the

following type (see example opposite):

a(b(d,e),c(,f(g,)))

a)

Write a Lisp function which generates this string

representation, if the tree is given as usual (as nil or

(X L R) expression). Then write a function which does

this inverse; i.e. given the string representation,

construct the tree in the usual form.

- P68

(**) Preorder and inorder sequences of binary trees

- We consider binary trees with nodes that are identified by

single lower-case letters, as in the example of problem P67.

a)

Write functions preorder and inorder that construct

the preorder and inorder sequence of a given binary tree,

respectively. The results should be lists, e.g. (A B D E C F G)

for the preorder sequence of the example in problem P67.

b)

Can you write the inverse of preorder from problem part a)

; i.e. given a preorder sequence, construct a

corresponding tree?

c)

If both the preorder sequence and the inorder sequence of

the nodes of a binary tree are given, then the tree is determined

unambiguously. Write a function pre-in-tree that does

the job.

- P69

(**) Dotstring representation of binary trees

- We consider again binary trees with nodes that are identified by

single lower-case letters, as in the example of problem P67. Such a

tree can be represented by the preorder sequence of its nodes in which

dots (.) are inserted where an empty subtree (nil) is encountered

during the tree traversal. For example, the tree shown in problem P67

is represented as "ABD..E..C.FG...". First, try to establish a

syntax (BNF or syntax diagrams) and then write functions

tree and dotstring which do the conversion.

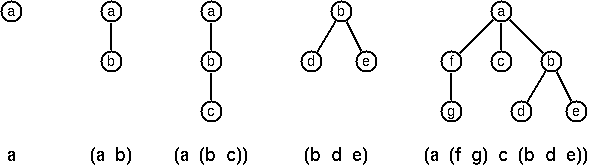

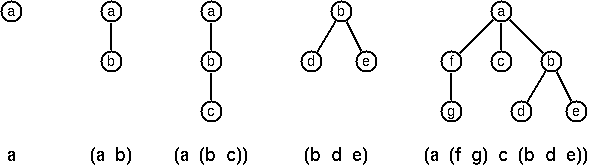

Multiway Trees

A multiway tree is composed of a root element and

a (possibly empty) set of successors which are multiway trees

themselves. A multiway tree is never empty. The set of successor

trees is sometimes called a forest.

In Lisp we represent a multiway tree by either a symbol (root with

no children) or by an expression (X C1 C2 ... CN), where X denotes

the root node and Ci denote each of the children.

The following pictures show how multiway tree structures are

represented in Lisp.

Note that in this Lisp notation a node with successors (children)

in the tree is always the first element in a list, followed by its

children.

- P70B

(*) Check whether a given expression represents a multiway tree

- Write a function istree which succeeds if and only if its argument

is a Lisp expression representing a multiway tree.

Example:

* (istree '(a (f g) c (b d e)))

T

- P70C

(*) Count the nodes of a multiway tree

- Write a function nnodes which counts the nodes of a given

multiway tree.

Example:

* (nnodes '(a f))

2

- P70

(**) Tree construction from a node string

- We suppose that the nodes of a multiway tree contain single

characters. In the depth-first order sequence of its nodes, a

special character ^ has been inserted whenever, during the

tree traversal, the move is a backtrack to the previous level.

By this rule, the tree in the figure opposite is

represented as: afg^^c^bd^e^^^

Define the syntax of the string and write a function (tree string)

to construct the tree when the string is given. Work with lists (instead

of strings). Write also an inverse function.

- P71

(*) Determine the internal path length of a tree

- We define the internal path length of a multiway tree as the

total sum of the path lengths from the root to all nodes of the tree.

By this definition, the tree in the figure of problem P70 has an internal

path length of 9. Write a function (ipl tree) to compute it.

- P72

(*) Construct the bottom-up order sequence of the tree nodes

- Write a function (bottom-up mtree) which returns the

bottom-up sequence of the nodes of the multiway tree mtree as

a Lisp list.

- P73

(**) Prolog-like tree representation

- There is a particular notation for multiway trees in Prolog.

Prolog is a prominent functional programming language, which is used

primarily for artificial intelligence problems. As such, it is one of

the main competitors of Lisp. In Prolog everything is a term,

just as in Lisp everything is a symbolic expression.

In Prolog we represent a multiway tree by a term t(X,F), where X

denotes the root node and F denotes the forest of successor trees

(a Prolog list).

The example tree depicted opposite is represented by the

following Lisp expression:

In Prolog we represent a multiway tree by a term t(X,F), where X

denotes the root node and F denotes the forest of successor trees

(a Prolog list).

The example tree depicted opposite is represented by the

following Lisp expression:

t(a,[t(f,[t(g,[])]),t(c,[]),t(b,[t(d,[]),t(e,[])])])

The Prolog representation of a multiway tree is a sequence of

atoms, commas, parentheses "(" and ")", and brackets "[" and

"]".which we shall collectively

call "tokens". We can represent this sequence of tokens

as a Lisp list; e.g. the Prolog expression t(a,[t(b,[]),t(c,[])]) could be

represented as the Lisp list ( t "(" a "," "[" t "(" b "," "[" "]" ")" "," t "(" c "," "[" "]" ")" "]" ")" ).

Write a function (tree-ptl expr) which returns the "Prolog

token list" if the tree is given as an expression expr in the usual

Lisp notation.

Example:

* (tree-ptl '(a b c))

( T "(" A "," "[" T "(" B "," "[" "]" ")" "," T "(" C "," "[" "]" ")" "]" ")" )

As a second, even more interesting exercise try to write

the inverse conversion: Given the list PTL, construct the corresponding

Lisp tree.

Graphs

A graph is defined as a set of nodes

and a set of edges, where each edge is a pair of nodes.

There are several ways to represent graphs in Lisp.

One method is to represent the whole graph as one data object. According

to the definition of the graph as a pair of two sets (nodes and edges), we

may use the following Lisp expression to represent the example graph:

One method is to represent the whole graph as one data object. According

to the definition of the graph as a pair of two sets (nodes and edges), we

may use the following Lisp expression to represent the example graph:

((b c d f g h k) ( (b c) (b f) (c f) (f k) (g h) ))

We call this graph-expression form. Note, that the lists are kept sorted,

they are really sets, without duplicated elements. Each edge

appears only once in the edge list; i.e. an edge from

a node x to another node y is represented as (x y), the expression (y

x)

is not present. The graph-expression form is our default representation.

In Common Lisp there are predefined functions to work

with sets.

A third representation method is to associate with each node the set

of nodes that are adjacent to that node. We call this the

adjacency-list form. In our example:

( (b (c f)) (c (b f)) (d ()) (f (b c k)) ...)

When the edges are directed we call them arcs. These

are represented by ordered pairs. Such a graph is called

directed graph. To represent a directed graph, the forms

discussed above are slightly modified. The example graph opposite

is represented as follows:

When the edges are directed we call them arcs. These

are represented by ordered pairs. Such a graph is called

directed graph. To represent a directed graph, the forms

discussed above are slightly modified. The example graph opposite

is represented as follows:

- Graph-expression form

- ( (r s t u v) ( (s r) (s u) (u r) (u s) (v u) ) )

- Adjacency-list form

- ( (r ()) (s (r u)) (t ()) (u (r)) (v (u)) )

Note that the adjacency-list does not have the information on whether

it is a graph or a digraph.

Finally, graphs and digraphs may have additional information attached

to nodes and edges (arcs). For the nodes, this is no problem, as we can

easily replace the single symbol identifiers with arbitrary symbolic

expressions, such as ("London" 4711). On the other hand, for

edges we have to extend our notation. Graphs with additional information

attached to edges are called labelled graphs.

- Graph-expression form

- ( (k m p q) ( (m p 7) (p m 5) (p q 9) ) )

- Adjacency-list form

- ( (k ()) (m ((q 7))) (p ((m 5) (q 9))) (q ()) )

Notice how the edge information has been packed into a list with

two elements, the corresponding node and the extra information.

The notation for labelled graphs can also be used for so-called

multi-graphs, where more than one edge (or arc) are allowed

between two given nodes.

- P80

(***) Conversions

- Write functions to convert between the different graph

representations. With these functions, all representations

are equivalent; i.e. for the following problems you can always pick

freely the most convenient form. The reason this problem is rated (***) is

not because it's particularly difficult, but because it's a lot

of work to deal with all the special cases.

- P81

(**) Path from one node to another one

- Write a function (path g a b) to return an acyclic path from

node a to node b in the graph g. The function should return all paths.

- P82

(*) Cycle from a given node

- Write a function (cycle g a) to find a closed path (cycle)

starting at a given node a in the graph g. The function should

return all cycles.

- P83

(**) Construct all spanning trees

- Write a function (s-tree graph) to construct

(by backtracking) all spanning trees

of a given graph. With this function, find out how many

spanning trees there are for the graph depicted to the left.

The data of this example graph can be found in the file

p83.dat.

When you have a correct solution for the s-tree function, use it to

define two other useful functions: (is-tree graph) and

(is-connected graph). Both are five-minutes tasks!

- P84

(**) Construct a minimum spanning tree

- Write a function (ms-tree graph) to construct a minimum spanning tree

of a given labelled graph. The function must also return the minimum weight.

Hint:

Use the algorithm of Prim. A small modification of the solution of

P83 does the trick. The data of the example graph to the right can

be found in the file p84.dat.

- P85

(**) Graph isomorphism

- Two graphs (n1 e1) and (n2 e2) are isomorphic if there is

a bijection f: n1 -> n2 such that for any nodes x,y of n1, x and y

are adjacent if and only if f(x) and f(y) are adjacent.

Write a function that determines whether two graphs are isomorphic.

Hint: Use an open-ended list to represent the function f.

- P86

(**) Node degree and graph coloration

- a) Write a function (degree graph node) that determines

the degree of a given node.

b) Write a function that generates a list of all nodes of a

graph sorted according to decreasing degree.

c) Use Welch-Powell's algorithm to paint the nodes of a graph

in such a way that adjacent nodes have different colors.

- P87

(**) Depth-first order graph traversal

(alternative solution)

- Write a function that generates a depth-first order graph

traversal sequence. The starting point should be specified,

and the output should be a list of nodes that are reachable from

this starting point (in depth-first order).

- P88

(**) Connected components

(alternative solution)

- Write a function that splits a graph into its connected components.

- P89

(**) Bipartite graphs

- Write a function that finds out whether a given graph is bipartite.

Miscellaneous Problems

- P90

(**) Eight queens problem

- This is a classical problem in computer science. The objective is to

place eight queens on a chessboard so that no two queens are attacking

each other; i.e., no two queens are in the same row, the same column,

or on the same diagonal.

Hint: Represent the positions of the queens as a list of numbers 1..N.

Example: (4 2 7 3 6 8 5 1) means that the queen in the first column

is in row 4, the queen in the second column is in row 2, etc.

Use the generate-and-test paradigm.

- P91

(**) Knight's tour

- Another famous problem is this one: How can a knight jump on

an NxN chessboard in such a way that it visits every square exactly

once?

Hints: Represent the squares by pairs of their coordinates of

the form (X Y), where both X and Y are integers between 1 and N.

Define a function (jump N (X Y)) that returns a list of the positions (U V)

such that a knight can jump from (X Y) to (U V) on a NxN chessboard.

And finally,

represent the solution of our problem as a list of N*N knight

positions (the knight's tour).

- P92

(***) Von Koch's conjecture

- Several years ago I met a mathematician who was intrigued by

a problem for which he didn't know a solution. His name was Von Koch,

and I don't know whether the problem has been solved since.

Anyway the puzzle goes like this: given a tree with N nodes

(and hence N-1 edges), find a way to enumerate the nodes from 1 to N

and, accordingly, the edges from 1 to N-1 in such a way that, for

each edge K, the difference of its node numbers equals K.

The conjecture is that this is always possible.

For small trees the problem is easy to solve by hand. However, for

larger trees, and 14 is already very large, it is extremely difficult

to find a solution. And remember, we don't know for sure whether there is

always a solution!

Write a function that calculates a numbering scheme for a given

tree. What is the solution for the larger tree pictured above?

- P93

(***) An arithmetic puzzle

- Given a list of integer numbers, find a correct way of inserting

arithmetic signs (operators) such that the result is a correct equation.

Example: With the list of numbers (2 3 5 7 11) we can form the

equations 2-3+5+7 = 11 or 2 = (3*5+7)/11 (and ten others!).

- P94

(***) Generate K-regular simple graphs with N nodes

- In a K-regular graph all nodes have degree K; i.e. the number

of edges incident to each node is K. How many (non-isomorphic!) 3-regular

graphs with 6 nodes are there? See also a

table of results.

- P95

(**) English number words

- On financial documents, like cheques, numbers must sometimes be

written in full words. Example: 175 must be written as one-seven-five.

Write a function (full-words n) to print (non-negative) integer numbers

in full words.

- P96

(**) Syntax checker

(alternative solution with difference lists)

-

In a certain programming language (Ada) identifiers are defined

by the syntax diagram (railroad chart) opposite.

Transform the syntax diagram into a system of syntax diagrams

which do not contain loops; i.e. which are purely recursive.

Using these modified diagrams, write a function (identifier str) that can

check whether or not a given string s is a legal identifier.

In a certain programming language (Ada) identifiers are defined

by the syntax diagram (railroad chart) opposite.

Transform the syntax diagram into a system of syntax diagrams

which do not contain loops; i.e. which are purely recursive.

Using these modified diagrams, write a function (identifier str) that can

check whether or not a given string s is a legal identifier.

* (identifier str) returns t when str is a legal identifier.

- P97

(**) Sudoku

-

Sudoku puzzles go like this:

Problem statement Solution

. . 4 | 8 . . | . 1 7 9 3 4 | 8 2 5 | 6 1 7

| | | |

6 7 . | 9 . . | . . . 6 7 2 | 9 1 4 | 8 5 3

| | | |

5 . 8 | . 3 . | . . 4 5 1 8 | 6 3 7 | 9 2 4

--------+---------+-------- --------+---------+--------

3 . . | 7 4 . | 1 . . 3 2 5 | 7 4 8 | 1 6 9

| | | |

. 6 9 | . . . | 7 8 . 4 6 9 | 1 5 3 | 7 8 2

| | | |

. . 1 | . 6 9 | . . 5 7 8 1 | 2 6 9 | 4 3 5

--------+---------+-------- --------+---------+--------

1 . . | . 8 . | 3 . 6 1 9 7 | 5 8 2 | 3 4 6

| | | |

. . . | . . 6 | . 9 1 8 5 3 | 4 7 6 | 2 9 1

| | | |

2 4 . | . . 1 | 5 . . 2 4 6 | 3 9 1 | 5 7 8

Every spot in the puzzle belongs to a (horizontal) row and a (vertical)

column, as well as to one single 3x3 square (which we call "square"

for short). At the beginning, some of the spots carry a single-digit

number between 1 and 9. The problem is to fill the missing spots with

digits in such a way that every number between 1 and 9 appears exactly

once in each row, in each column, and in each square.

- P98

(***) Nonograms

-

Around 1994, a certain kind of puzzles was very popular in England.

The "Sunday Telegraph" newspaper wrote: "Nonograms are puzzles from

Japan and are currently published each week only in The Sunday

Telegraph. Simply use your logic and skill to complete the grid

and reveal a picture or diagram." As a Lisp programmer, you are in

a better situation: you can have your computer do the work! Just write

a little program ;-).

The puzzle goes like this: Essentially, each row and column of a

rectangular bitmap is annotated with the respective lengths of

its distinct strings of occupied cells. The person who solves the puzzle

must complete the bitmap given only these lengths.

Problem statement: Solution:

|_|_|_|_|_|_|_|_| 3 |_|X|X|X|_|_|_|_| 3

|_|_|_|_|_|_|_|_| 2 1 |X|X|_|X|_|_|_|_| 2 1

|_|_|_|_|_|_|_|_| 3 2 |_|X|X|X|_|_|X|X| 3 2

|_|_|_|_|_|_|_|_| 2 2 |_|_|X|X|_|_|X|X| 2 2

|_|_|_|_|_|_|_|_| 6 |_|_|X|X|X|X|X|X| 6

|_|_|_|_|_|_|_|_| 1 5 |X|_|X|X|X|X|X|_| 1 5

|_|_|_|_|_|_|_|_| 6 |X|X|X|X|X|X|_|_| 6

|_|_|_|_|_|_|_|_| 1 |_|_|_|_|X|_|_|_| 1

|_|_|_|_|_|_|_|_| 2 |_|_|_|X|X|_|_|_| 2

1 3 1 7 5 3 4 3 1 3 1 7 5 3 4 3

2 1 5 1 2 1 5 1

For the example above, the problem can be stated as the two lists

((3) (2 1) (3 2) (2 2) (6) (1 5) (6) (1) (2)) and

((1 2) (3 1) (1 5) (7 1) (5) (3) (4) (3)) which give the

"solid" lengths of the rows and columns, top-to-bottom and

left-to-right, respectively. Published puzzles are larger than this

example, e.g. 25 x 20, and apparently always have unique solutions.

- P99

(***) Crossword puzzle

-

Given an empty (or almost empty) framework of a crossword puzzle and

a set of words. The problem is to place the words into the framework.

The particular crossword puzzle is specified in a text file which

first lists the words (one word per line) in an arbitrary order. Then,

after an empty line, the crossword framework is defined. In this

framework specification, an empty character location is represented

by a dot (.). In order to make the solution easier, character locations

can also contain predefined character values. The puzzle opposite

is defined in the file p99a.dat, other examples

are p99b.dat and p99d.dat.

There is also an example of a puzzle (p99c.dat)

which does not have a solution.

The particular crossword puzzle is specified in a text file which

first lists the words (one word per line) in an arbitrary order. Then,

after an empty line, the crossword framework is defined. In this

framework specification, an empty character location is represented

by a dot (.). In order to make the solution easier, character locations

can also contain predefined character values. The puzzle opposite

is defined in the file p99a.dat, other examples

are p99b.dat and p99d.dat.

There is also an example of a puzzle (p99c.dat)

which does not have a solution.

Words are strings (character lists) of at least two characters.

A horizontal or vertical sequence of character places in the

crossword puzzle framework is called a site.

Our problem is to find a compatible way of placing words onto sites.

Hints: (1) The problem is not easy. You will need some time to

thoroughly understand it. So, don't give up too early! And remember

that the objective is a clean solution, not just a quick-and-dirty hack!

(2) Reading the data file is a tricky problem for which a solution

is provided in the file

p99-readfile.lisp. Use the function

read-lines, which returns the words and the grid in a 2-element list.

(3) For efficiency reasons it is important, at least for

larger puzzles, to sort the words and the sites in a particular order.

For this part of the problem, the solution of

P28 may be very helpful.

Last modified: Thu Sep 19 07:02:13 BRT 2013

In this layout strategy, the position of a node v

is obtained by the following two rules:

In this layout strategy, the position of a node v

is obtained by the following two rules: An alternative layout method is depicted in the illustration

opposite. Find out the rules and write the corresponding

Lisp function. Hint: On a given level, the horizontal

distance between neighboring nodes is constant.

An alternative layout method is depicted in the illustration

opposite. Find out the rules and write the corresponding

Lisp function. Hint: On a given level, the horizontal

distance between neighboring nodes is constant. Yet another layout strategy is shown in the illustration

opposite. The method yields a very compact layout while

maintaining a certain symmetry in every node. Find out

the rules and write the corresponding Lisp function.

Hint: Consider the horizontal distance between a node and its

successor nodes. How tight can you pack together two subtrees to

construct the combined binary tree?

Yet another layout strategy is shown in the illustration

opposite. The method yields a very compact layout while

maintaining a certain symmetry in every node. Find out

the rules and write the corresponding Lisp function.

Hint: Consider the horizontal distance between a node and its

successor nodes. How tight can you pack together two subtrees to

construct the combined binary tree?

One method is to represent the whole graph as one data object. According

to the definition of the graph as a pair of two sets (nodes and edges), we

may use the following Lisp expression to represent the example graph:

One method is to represent the whole graph as one data object. According

to the definition of the graph as a pair of two sets (nodes and edges), we

may use the following Lisp expression to represent the example graph:

When the edges are directed we call them arcs. These

are represented by ordered pairs. Such a graph is called

directed graph. To represent a directed graph, the forms

discussed above are slightly modified. The example graph opposite

is represented as follows:

When the edges are directed we call them arcs. These

are represented by ordered pairs. Such a graph is called

directed graph. To represent a directed graph, the forms

discussed above are slightly modified. The example graph opposite

is represented as follows:

In a certain programming language (Ada) identifiers are defined

by the syntax diagram (railroad chart) opposite.

Transform the syntax diagram into a system of syntax diagrams

which do not contain loops; i.e. which are purely recursive.

Using these modified diagrams, write a function (identifier str) that can

check whether or not a given string s is a legal identifier.

In a certain programming language (Ada) identifiers are defined

by the syntax diagram (railroad chart) opposite.

Transform the syntax diagram into a system of syntax diagrams

which do not contain loops; i.e. which are purely recursive.

Using these modified diagrams, write a function (identifier str) that can

check whether or not a given string s is a legal identifier. The particular crossword puzzle is specified in a text file which

first lists the words (one word per line) in an arbitrary order. Then,

after an empty line, the crossword framework is defined. In this

framework specification, an empty character location is represented

by a dot (.). In order to make the solution easier, character locations

can also contain predefined character values. The puzzle opposite

is defined in the file

The particular crossword puzzle is specified in a text file which

first lists the words (one word per line) in an arbitrary order. Then,

after an empty line, the crossword framework is defined. In this

framework specification, an empty character location is represented

by a dot (.). In order to make the solution easier, character locations

can also contain predefined character values. The puzzle opposite

is defined in the file